I worry almost constantly about the ways that the pandemic – which was traumatic and disturbing for everyone – has set a precedent for our collective ability to avoid thinking about the well-being of others.

Prior to COVID, we were already living in a very dehumanizing, death-making, and callous society. I think all the time about the disappearance of 1.9 million people to imprisonment at any given moment in the United States. These people live in cages, yet many of us on the outside do not dwell on their existence. I think of the multitudes of people – the full count unknown but being in the hundreds of thousands or above — who were killed by the U.S. war in Iraq, a war that was started by a straight-up lie. Many of us knew it was a lie, but we learned to live with that reality (if unwillingly). And then there are the more than 650,000 people living on the streets. Most of us have learned to step over these neighbors, to look away from this reality, in order to go on with our own lives.

This society is one that forces us to draw a distinction between our own satisfaction and the lack that others experience, because no amount of personal sacrifice by a working person can fill the lack. It is by design that some of us have houses, food, and objects that give us pleasure while other people struggle for water, because that society allows a select few to have private jets and to establish or maintain dynasties for their families.

The result is that we are forced to accept the need, deprivation, and violence, that others experience and to figure out for ourselves how to negotiate that acceptance. This has been true for at least my lifetime. It’s true that throughout that time new levels of deprivation have come and gone that we have, in general, accepted. But the pandemic was another level. The number of people who died – vanished from this earth – in a period of months was previously unfathomable. We lived the Monty Python “bring out your dead” skit becoming reality as morgues across the United States and across the world were unable to keep up with the pace of death. And so it took us a while to understand – if we have understood it — that while so many were dying, even more were being disabled, having their lives changed forever in profound ways, in a society that discards disabled people.

The emergence of the COVID pandemic was a shock, a major hit to just about everyone’s psyche and worldview, even if it seems naïve to admit that now (it does). Confronting suffering on a new scale changed us.

It is absolutely wild to think that now, when I think of the early days of the pandemic or when I hear people talk about that spring of 2020, what we mostly talk about is the ways we were stuck in our homes or had trouble buying certain products. I don’t hear people talk about (and I don’t often talk about) the absolute stark and sudden fear that I felt wondering which of my friends, and how many, might be snatched away suddenly. The horror and dread that I felt waking up every day to a world in which tens of thousands were dying on top of the already harsh, violent, and dehumanizing world I lived in. The pain of trying to assimilate this new horror. The confusion and fear of constantly changing information and directives about how to protect ourselves and each other, and the utter anxiety of all of us being subject to a disease about which little was really known.

It is also worth recalling that the human desire to care for each other came to the forefront and seemed to bloom all over, as it often does in crisis.

We do not, though, talk much about how the pandemic is in many ways our first real step into the absolute chaos of climate crisis. Not only because the ability for an illness like this to spread is itself the result of changes in our climate, but because it showed us what it will be like when large-scale disasters impact our distribution systems. We don’t talk much about this, but it is there, looming.

We all experienced the organized abandonment and collapse in this crisis, and we are still experiencing it. All of us are watching in real-time as our loved ones become more and more likely to have a permanent disability through multiple infections. We are more or less aware of the more than one thousand people still dying every week, although we are less aware because the data simply isn’t available. Not only is it hard to find, it simply isn’t being collected. This is intentional and it is key: if we can’t accurately describe what’s going on, it’s not only hard for us to organize around it, but the fact itself becomes up for debate. It becomes optional to accept this.

And all of this – the deepening push to abandon, the increased normalization of preventable disasters — has led to the situation now, where we are witnessing a genocide in real-time. Thousands of people are being killed in a month again, this time in a tiny strip of land and in a direct, targeted, and above all, completely preventable way. More than 32,000 people have been killed by Israel since October 7, as of today In this case, it is Palestinians who are being killed (we are not all potentially susceptible), but then again, this massacre is preventable – including by the United States government. And we all know that it is happening, whether we choose to entertain that awareness or not.

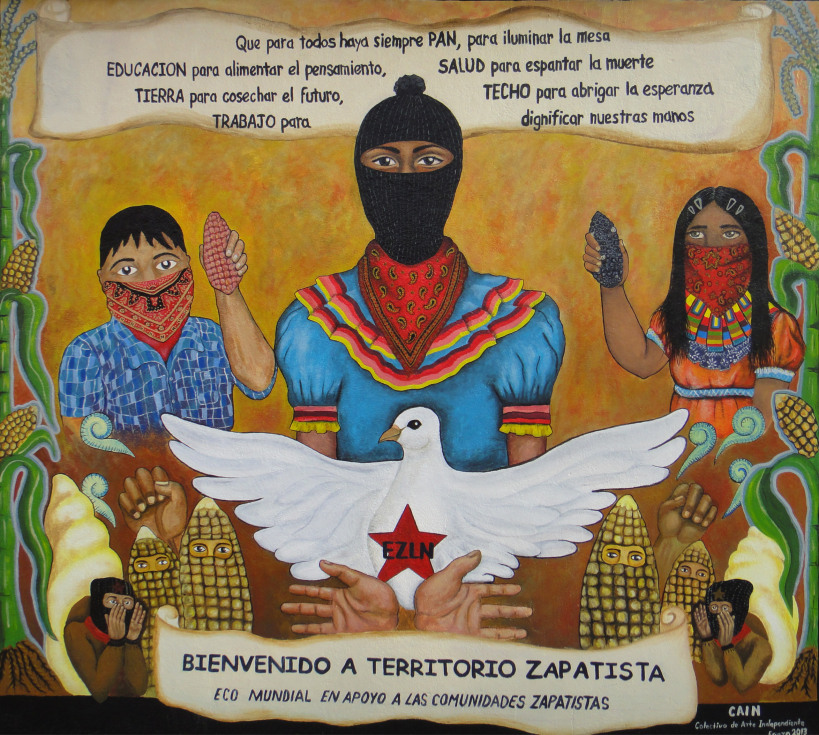

We are now prepared to accept a genocide. This thing, this awful awful thing, will not be the last or the worst thing, at least not unless we refuse to abandon each other. As Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba emphasize in Let This Radicalize You, the future is not written, and it does not have to be this way. We do not know what will happen, and that is a powerful, hopeful thing. But if we do not want a future even worse than this one – one with even more catastrophic loss of life and health — we must absolutely refuse the many ways we are conditioned to abandon each other and look away.